The first time I tasted a detail of India was when I received an unfinished half of a pomegranate and had to coax the flesh out of the fruit's caverns. I used my fingers, swollen from airplane travel, to chunk off the rough skin to nestled rubies clinging together like fish eggs in coral. Their color and sweetness was inviting, yet entombed bitter seeds. I came to find my impression of India the same. Upon pulling back rough expectations, sweet flesh was exposed, but there was bitter crunch as well. It is the details that define a place, and any food.

"The commercials held our interest as much as any show, for they let us know what we should be eating, playing, and wearing. They let us know how we should be." ~ Bich Minh Nguyen

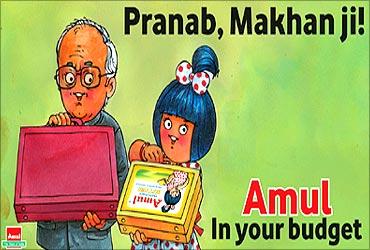

When first going to India, I was overwhelmed. We had been traveling for the equivalent of three days with virtually no sleep, had left 90 degree weather back in Chicago for 125 and humid, and immediately experienced first hand what a monsoon does to traffic on our way back to Nirman's campus. For humans, it huddles them under cubicle-like store fronts, or hitches up ankle long pants and saris and silk chemises to mid-thigh to avoid the infested calf-deep water. For autos and motorbikes, it brings them to a standstill or turns the smaller ones into figurative jetskis. As a human huddled in an auto, I was assaulted with ads like the red and white of "Airtel" and the blue haired Amul girl with her dairy products. These labels and colors sought my attention, much like Pringles did for Bich and her sister Anh when they interacted with the Heidengas. They focused on local companies like Ford and Amway to settle in their roots, and fell in love with Purple Cow ice cream and other brightly colored and recognized brands. I looked for coca cola advertisements in Hindi. Bich experienced firsthand the power of labels and their comforting nature, or lack thereof, such as in clothing brands, or how kids in their neighborhood would boast about going to McDonalds 3 times in one week. I myself went to McDonalds while in India, just to see how it would be different. Even I recognized McDonalds as an American symbol all these years later. I ordered a number 4, a paneer burger with a sealed off far too watery orange juice on the side; it was better than combatting the fear of unfiltered water. The most evident difference was that McDonalds was considered one of the more classy and dignified places to dine in India, and that paneer is something I enjoy eating, but do not think of as a substitute for the burger I enjoy back at home.

Bich wanted to savor new food, different food, white food. I wanted to savor new food, different food, food that I was used to being produced at restaurants like Saffron or Shalimar. I expected what I had found at Americanized Indian institutions full of curry and spices and familiar tastes with a new spin on them. Instead, we were given authentic food. Luckily, I quickly embraced the self-washed tin trays whose compartments would hold naan, rice, and sauces full of spices. Every meal, although functioning the same, had its own uniqueness to it. One time I sat in the kitchen to watch the cooks boil the Chai Tea, where they dumped old leaves, milk, water, and sugar in the same pot, and I was fascinated by their use of everything. We couldn't speak much to each other with our limited vocabularies, but we were able to speak through food. Thank you was not a common phrase in India. You showed your appreciation, and ate with your fingers and tongue to catch every last dribble, the same way food was prepared, using everything.

For Bich, the combination of Vietnam's ancient matrilineal roots, Confucianism, and Western influences made for a modern-day balance of control and deference in every household. For me, India was a balance between its ancient history, western influences from where I came from, and a general consensus in kindness and welcome. I saw echoes of what I knew and loved and hated; the combination of advertisements and buildings balanced precariously with bamboo scaffolding echoed the New York City I hold close; the bright saris and clothing that always looks black-tie ready reminded me of rummaging in my mother's dresses as a child; the field of trash heaps that the cow crossed the street to reach to hunt for grass. It was the details, the moments and gestures, like the stall keeper who placed a bracelet made of plastic nut-seeds and red string used on children's toys onto my wrist, tightening the string with the hushed, "So shiva will protect you". It was the man who gruffly scrunched his nose at me like a predator when I looked at him for too long during stopped traffic, and how I still wonder if it was an angry challenge or a misread expression. It was the moment where I realized that the mountains of trash were more biodegradable and earth friendly than any trash can or recycle bin that I had grown accustomed to in America. It was these details that pulled me away from the cliff bars bought at REI and introduced me to the experience of fighting a pomegranate for both its bitter and sweet moments, because every flavor was worth it.

What a gorgeous response, McKenna! I loved learning about your experience to India through the vivid details you shared--and how you artfully connected it to the text. You have shown how those who have been deemed "other," "outsider" or "different" automatically find a connection to each other, just as Bich connected with other children of color or those who didn't fit the mythical norm in other ways.

ReplyDeleteI love how you thread wrestling with a pomegranate throughout your response. I also love how you compare your drive for new foods with that of Bich's in her book. You do a good job of connecting multiple cultures: Bich's Vietnamese and Westernize tastes, Indian cuisine, and the food you experienced as you grew up.

ReplyDelete